Photo by Boston University Photography.

Special thank you to Bernie Corbett for his help in the reporting of this story.

With the ink still wet on his new contract, Jack Parker tread behind athletic director Warren Schmakel and into the Boston University men’s hockey locker room.

“Guys, listen up,” Schmakel told the team. “We fired Leon Abbott, and Jack Parker is your new head hockey coach. Good luck.”

Schmakel walked out, and the Parker era had officially begun — whether the new bench boss was ready for it or not.

“I was almost flabbergasted,” Parker told The Boston Hockey Blog. “The guys were just sitting in their chairs staring at me. I looked at them and said ‘Hey, it’s 9:25 and practice is at 10:00, make sure you’re on the ice on time.’ And I walked out.”

The 28-year-old Parker was called into Schmakel’s office at 8 a.m. that morning – exactly 50 years ago, on Friday Dec. 21, 1973 – two hours before the Terriers were scheduled to practice for the upcoming holiday tournament at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

An eligibility controversy involving Terrier players Dick Decloe, Bill Buckton and Peter Marzo cut Abbott’s BU career short after one full season (1972-73) and put Parker in charge seemingly overnight. While Parker had spent the last year as the head coach of the “B” team and served as an assistant on the varsity squad for the three prior seasons under Jack Kelley, this was an entirely new task.

“I was upset for Leon who, to this day, got absolutely a raw deal at BU, and obviously it was to my benefit,” Parker said. “He was a good guy and a good friend and he got screwed. But I was head coach, and we had to win a hockey game.”

After addressing the team, Parker walked down the hall, into the coach’s room, and began to put his skates on for practice when there was a banging on the tall steel door.

Boom. Boom. Boom.

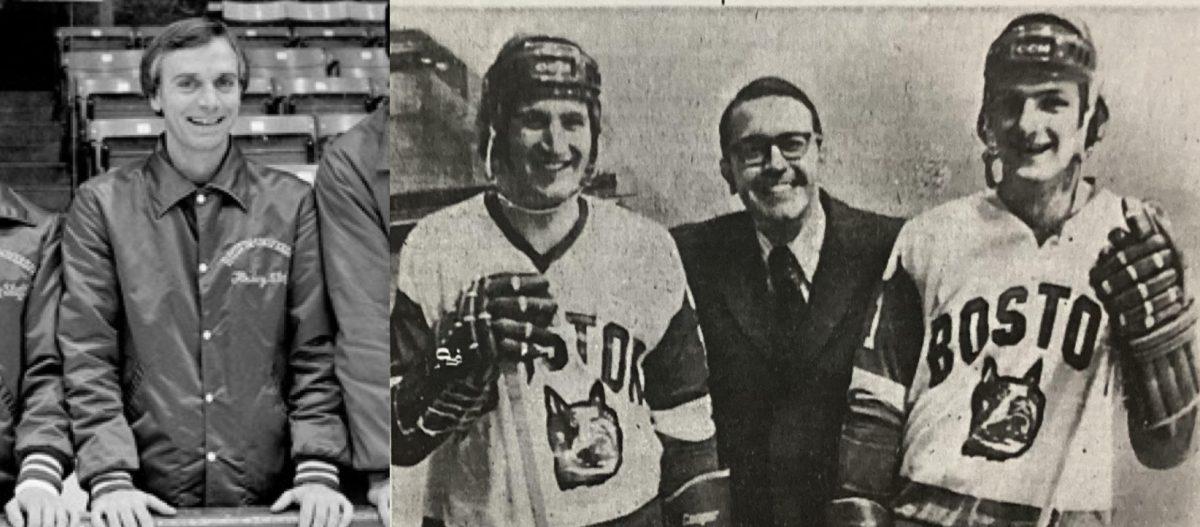

Parker got up and opened the door. It was freshman forward Mike Eruzione, and he had a question for his new head coach – could he get a new pair of skates? Eruzione explained that Abbott didn’t allow him to because he wasn’t sure if he was going to make the team.

“I said ‘Well Mike, I’m really sure you’re going to make the team, so go see Carl James our equipment manager and get a new pair of skates,’” Parker said. “He walked out, and I just sat there thinking ‘Wow, the king is dead, long live the king.’”

Parker went on to win his first game as head coach six days later on Dec. 27, 1973 in a 3-1 match against Dartmouth College. But that’s far from where the story started or ended.

Cornell Blows Whistle on Dick Decloe

Sophomore forward Dick Decloe came into Cornell University’s Lynah Rink on Dec. 13, 1972 and scored a hat trick en route to BU’s 9-0 win over the Big Red. The drubbing marked the Terriers’ first-ever win at Lynah Rink.

A few weeks later, Decloe was ruled ineligible to play NCAA hockey.

Following the blowout on home ice at the hands of the Terriers – who had beaten Cornell 4-1 at Boston Garden on March 11, 1972 to win their first-ever ECAC championship before topping them again a week later, March 18, 1972, 4-0 to secure their second consecutive national title – athletic director Jon T. Anderson filed a complaint with the ECAC concerning Decloe’s eligibility.

Decloe played Junior A hockey for the OHL’s London Knights in the 1970-71 season, and unbeknownst to him or his family, Decloe’s team had paid his high school, non-resident tax of $189.33. The NCAA established a rule in 1972 that Junior A players could not receive money from the team they were playing for – albeit, the $189.33 did not go into Decloe’s pocket, and was a standard process handled prior to the season.

Warren Schmakel and Leon Abbott called Decloe into the athletics office to deliver the news.

“All I remember is the looks on their faces and they said ‘We have a problem,’” Decloe said in an interview with Bernie Corbett, the voice of BU hockey. “They mentioned that somebody had complained and whatnot, and from that point on, I wasn’t allowed to step on the ice until they resolved the matter.”

The matter, however, was never resolved. Decloe was ruled ineligible in late January of 1973 and the Terriers were forced to forfeit the 11 games Decloe had played in, sinking their record to from 11-2-0 to 0-13-0.

“Nobody had raised a red flag and said, ‘If we’re going to do this, we have to keep it quiet,’” Decloe said. “There were other guys that had went ahead of me – you could play Junior A and you could go to university at the time. I don’t think anyone had heard of this high school tax thing before.”

After all, Decloe’s brother, Jack Decloe, played college hockey from 1969-72 at RPI under Abbott, and had no issue.

Anderson – Cornell’s athletic director – and head coach Dick Bertrand insisted the call-out was to ensure fair play in the NCAA. One of their players, Peter Titanic, was declared ineligible the previous season due to similar Junior A circumstances as Decloe.

Whether the fact that Decloe was recruited by Cornell, chose to play for its rival, BU, and then hung three on the Big Red in the team’s worst loss in program history had any effect on the whistle blowing – I’ll let you decide.

“My decision was if that’s the way it’s gonna be, that’s the way it’s gonna be and I’ll have to just figure something else out,” Decloe said. “Life goes on, and lucky for me, I got picked up by the Toronto Marlboros about a week later.”

Decloe proceeded to win the Memorial Cup with the Marlboros at the end of the 1972-73 season in which he posted 21 points (eight goals, 13 assists) in 17 games but was forced to leave his BU career behind.

Of note, Mark and Marty Howe – hockey legend Gordie Howe’s sons – played on that Memorial Cup-winning team with Decloe.

In the aftermath of Decloe’s departure, Schmakel asked Abbott if there were any other players on BU’s roster that may also be in danger of ineligibility. Abbott gave two names: Bill Buckton and Peter Marzo.

Buckton and Marzo Pulled into the Fire

Freshman forwards Bill Buckton – from Southampton, Ontario – and Peter Marzo – from Acton, Ontario – quickly got caught in the eligibility crossfires. The two had ties to playing Junior A hockey the season prior to arriving at Boston University and were ruled ineligible by the NCAA in the spring of 1973 before leaving for summer.

“I remember saying to Leon when the Decloe thing was going down, ‘We oughta send Buckton and Marzo home,’” Parker said.

“I said the same thing is going to happen to them. And the problem is, if you keep them around you’re going to fall in love with these two kids because they’re great guys and they’re really good players.”

Buckton and Marzo, who had been playing for Parker on the freshman “B” team during the 1972-73 season, packed up their things and searched for the next step. With the help of Parker, Marzo was poised to continue his education at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario, and Buckton was exploring his options at the University of Western Ontario and University of Toronto.

“We were stunned,” Marzo told The Boston Hockey Blog.

Then, the phone rang. On the other end was Gordon Martin – a lawyer the Friends of BU Hockey had hired to fight the NCAA’s ineligibility ruling on Buckton and Marzo. The two 19-year-olds drove into Toronto that summer to meet Martin at the Royal York Hotel and delve into the details of their potential case. After hours of questioning, Martin decided to take it on.

Martin got Buckton and Marzo an injunction – ruled by federal judge Joseph Tauro – to continue to play for BU while the court case proceeded in the 1973-74 season.

“Bill and I spent a lot of time doing depositions, trying to meet with Gordon,” Marzo said. “There were a lot of times, especially at the beginning, we were in court. It was demanding but doable. You played hockey, you did your school work and this was like a part-time job.”

Buckton and Marzo’s depositions detailed the teams they played for before BU and the money allotted to them – $24 a week for room and board that went to the landlord or billet and $10 for weekly expenses.

Buckton skated in a handful of early-season Junior A games for the Oshawa Generals before getting injured, and returned to Junior B for the rest of the season so he could play closer to home. Marzo started the 1971-72 season with the Junior A Kitchener Rangers, but a coaching change cut his ice time and he, too, returned to Junior B hockey that year.

The two could barely be classified as Junior A players – and even so – there were hundreds of NCAA hockey players getting by under their same circumstances. With their argument and evidence prepped, Buckton, Marzo and Martin began litigation on Oct. 11, 1973, and the full trial of the case began March 25, 1974.

Case Hits the Court, Out with Abbott

The root of the debate stemmed from the NCAA’s hypocrisy between American and Canadian hockey players. A U.S. kid that received scholarship money to play at prep school and further its game before college was eligible to play. However, a Canadian kid that went through the equivalent process across the border was ineligible.

Growing up, Marzo’s hometown of Acton, Ontario had a total population of about 3,500. To reach the next level in hockey and eventually get recruited for college, he had to leave – as did Buckton. Juniors was the only option.

“If they’re saying to keep your eligibility you had to play within your town, well, the one year we didn’t even have enough players to make a team,” Marzo said. “I’m not going to play a high level of hockey there in any way.”

In the court deliberations, Martin revealed there were over 140 Canadian players throughout college hockey that had also received room and board while playing Junior A, and that by the NCAA’s ruling, they, too, would be deemed ineligible.

“I’d go on the ice and go over to the faceoff circle and I’d look at the guys across from me and he would say, ‘Buck, thanks for not squealing on me,’” Buckton told The Boston Hockey Blog. “I didn’t want anyone else to kind of have that on their shoulders.”

Buckton and Marzo continued their regular varsity team programming while fighting their case, and while the ice felt like the one place things were okay, it weighed heavy on the youngsters.

“It was pretty tough. I thought I was in court more than I was in school,” Buckton said. “I’ll tell you, I broke down a couple times. Thank God I had a person that was a facilitator saying ‘Okay, this guy needs a break.’”

Coach Abbott was called into court to testify in December of 1973. His honesty sealed his fate at BU. On the stand, Abbott was questioned about his due diligence when recruiting Buckton and Marzo.

“Leon said to me, ‘They asked me, why didn’t you ask them if they got room and board?’ And Leon truthfully told them, ‘Because I didn’t want to know the answer,’” Parker said.

Abbott was fired that week, and Parker was hired. Amidst the mess, the team gained a new leader to follow – and for Buckton and Marzo specifically – it made all the difference.

“He bled BU. He was training under Jack Kelley and then he just took over and he just ran it the way he wanted to run it. It was the best thing ever for BU hockey,” Buckton said.

Parker Enforces Early Success, Sense of Normalcy

Parker took the reins and immediately silenced the outside noise. To him, and everyone else in the BU room, Buckton and Marzo were simply hockey players, teammates and key pieces to the Terriers’ success.

“We didn’t talk about it. Coach Parker didn’t come into the room and start talking about the court case or even pull us aside and talk about the court case,” Marzo said. “He didn’t want that added pressure on us, and he didn’t want the added pressure on the team. We kept it pretty separate.”

The court case wasn’t officially dropped until August 1977 after Buckton and Marzo had both graduated. While the two were able to complete their four years as Terriers under the injunction, once they were out of the NCAA, the case no longer held merit.

“The NCAA decided, in typical NCAA fashion, they just put the case on hold. They never went to a conclusion because they didn’t want to get proven wrong,” Parker said. “So that was a way for them to keep their rule. But they never enforced the rule ever again and then finally they threw it out.”

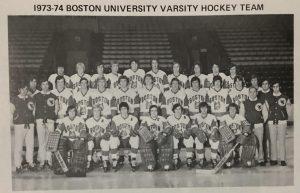

What could’ve been a distraction for Parker and the Terriers was anything but. BU went on to win consecutive ECAC championships in 1974, 1975, 1976 and 1977, and appeared in the Frozen Four in all four of those years.

“[Parker] just held everything together that whole year,” Marzo said.

En route to the conference title in 1973-74, BU played Cornell for the first time since the program called out Decloe and, in hand, triggered the Buckton and Marzo controversy. The Terriers swiftly disposed of the Big Red 7-2 on Jan 23, 1974 and 7-3 on March 8, 1974 in the ECAC semifinals before beating Harvard 4-2 in the finals.

“The BU-Cornell games were the big rivalry. But that threw lighter fluid on the rivalry, that’s for sure,” Parker said.

An Unlikely Friendship

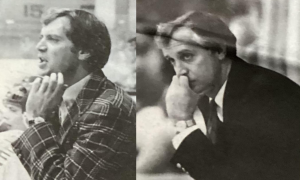

Winning records masked any growing pains Parker might’ve had in his first few seasons as head coach, but one particular friendship made the adjustment a whole lot easier.

Bill Cleary, who was head coach of the Harvard University men’s hockey team from 1971-1990, had previously recruited Parker to go to Harvard well before he got his job behind the bench for the Crimson. Now colleagues, the dynamic shifted.

“I really got to know him once I became the head coach because I was kind of blindsided by not being prepared for the next game so to speak, kind of recruiting,” Parker said.

BU and Harvard were the two best teams in the East for the next couple of years – and rivals because of proximity – but it didn’t stop Parker and Cleary from helping each other out in terms of scouting.

“Let’s say he played Brown a week ago and we were going to play Brown next Friday, I would call Billy and say ‘What can you tell me about Brown?’ We got into a relationship of trading information right off the bat. He would call me and ask me for information about who he was playing,” Parker said.

During a time in which Parker was learning what it took to be a varsity head coach while actively fulfilling the position, Cleary was a constant supporter.

“For me it started almost as an unbelievable necessity,” Parker said. “Billy really helped me out there, and to this day we are close friends.”

The Parker Legacy, 50 Years Later

The beginning of Parker’s head coaching career at BU wasn’t necessarily part of a mapped out plan, but man, did it work out.

Parker – who boasts the most wins at one school with 897 – was at the helm for 40 years from 1973-2013, setting a standard of excellence for Terrier hockey that each year’s team strives to match and surpass. Three national championships, 11 conference titles and 21 Beanpot trophies define the Parker era in terms of hardware, but it’s the gritty, relentless and prideful culture created that truly marks his time at BU.

“I played hockey for Jack and for Boston University, that’s all I focused on,” Marzo said. “Coach Parker was a definite inspiration and a mentor in my life in a lot of things. When he asked me to do things, I would do it – I wouldn’t even question.”

Buckton, who has gone on to run a hockey school business for the last 42 years and has taught minor hockey for 32 years, still leans on his time as a Terrier under Parker.

“Honest to God, I still follow some of Jack’s practices that we did. The way we set it up, the way we thought everything out, how he put all these little things together,” Buckton said. “I had them doing BU practices specifically, because I knew they worked.”

Beyond the X’s and O’s, trophies and historic games, though, is the fact that BU hockey players never truly leave the program. That’s because Parker had his guys playing for something bigger than themselves. It’s what fuels Terrier hockey to this day.

“Boston University hockey is one thing,” Marzo said. “The Boston University family is something that I had never encountered in my life before.”

Peter Fornatale • Jan 3, 2024 at 8:55 am

Very well written piece that explains the complicated origins of Coach Parker’s legacy in a clear and entertaining way. I look forward to reading more from Belle Fraser.

Doug Chapman • Dec 25, 2023 at 10:21 pm

Dick Decloe played for France in the 1980 Olympics, so the Olympics had no problem with him being an amateur.

Aubrey Ferguson • Aug 19, 2025 at 12:33 am

He played for The Netherlands in the Olympics but the intent of your observation is accurate.

Jim McKenzie • Dec 23, 2023 at 10:42 pm

This is a very well written and researched article that documents how very much Jack did for the BU program, the standards he set and the legacy he leaves. Reading it brought back many great memories of events over the Parker years. Congratulations and thanks for a wonderful article.